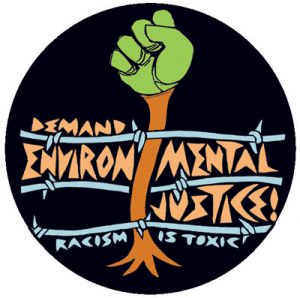

Environmental Justice

Environmental justice defined by the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice as the “reassurance that all people, regardless of race, national origin or income, are protected from disproportionate impacts of environmental hazards” (Holifield 2001). However, when thinking of environmental impacts on health, the US falls behind several other industrialized nations on overall health, despite large budgets being spent on healthcare compared to any other nation (Brulle and Pellow 2006). Recently, in the realm of public health, research has started to look into exposure to environmental pollution and assess the contributions it has towards health inequalities, and it has been seen that many communities of color, or lower socioeconomic status tend to be located closer to environmentally hazardous areas and are being exposed to toxins (Brulle and Pellow 2006). The range of health impacts experienced through pesticides can range from minor to major, including injury to the nervous system, lungs, reproductive organs, dysfunction of the immune system, and birth defects (Landrigan et al. 1999).

An example, of an issue of environmental justice can be discussed in a paper by Wolfard on unequal land access in Brazil (2008). Brazilian agriculture is an example of an environmental justice issue as the geographic scale has been recognized to be socially, politically, and economically structured (Wolfard 2008). As large soybean production began in the Brazilian cerrado, science agriculture, industry, and the state all joined together to encourage and support the production of this commodity by urbanizing the area with new roads, biotechnology innovations, and government subsidies. This encouraged agricultural commodity producers to carve out large-scale farms along rivers and roads to link the cerrado with further production, marketing, and distribution worldwide, despite this area being considered unsuitable for small-scale farm production (Wolfard 2008). Additionally, in regards to the actions previously mentioned, “this deliberate work at the level of the nation-state underlies the procedural inequities that have turned producers and simultaneously threatened the ecological sustainability of production in the region” (Wolfard 2008). This study concludes that if popular demand for land distribution was acknowledged earlier in time, or if resettlement within rural areas in addition to support of smaller scale cultivation of products for local markets by the government would have occurred, large farms would have little “natural” advantage over the smaller farms that are seen throughout cerrado (Wolfard 2008).