Conservation of Lions and Tigers and Bears, Oh My! But…What About the Other Guys?

by Emily Kurtz and McKenzie Somers, November 6, 2019

GETTYSBURG, PA – “Isn’t the symbol for world wildlife conservation the panda?” asks Lauren Heyer, a junior Psychology major at Gettysburg College.

Like Heyer, many students have similar mindsets about the current biodiversity crisis impacting the entire planet. When asked about biodiversity loss, Kelly Curran, a Gettysburg College senior philosophy major said, “I regret to say I don’t really know much about the extinction crisis.” This was a similar sentiment for a multitude of students, each struggling to come up with examples of endangered or threatened species. Panda bears and koala bears were among the most named species that students recognized as endangered.

“I regret to say I don’t really know much about the extinction crisis”

– Kelly Curran, 2020

Though, it isn’t just students. Conservation efforts as a whole have shifted towards focusing on the charismatic species, taking attention away from species that people don’t really know much about.

According to a master’s review published by Ducarme et al. in 2012, in conservation terms, a charismatic species is defined as “basically large mammals and vertebrates with some attractive traits for the human population considered.”

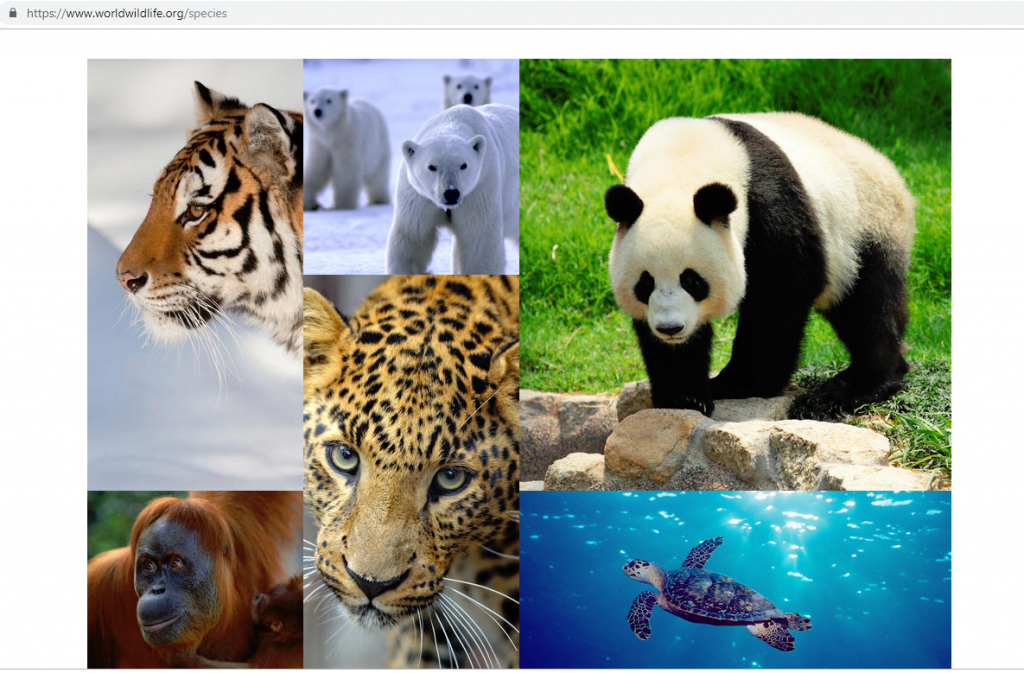

If you’ve ever taken a look at the World Wildlife Fund’s website, you’ll find numerous photographs of tigers and turtles. Like Heyer was referring to, their logo is even a panda. These species are the poster children for wildlife conservation. They often have human characteristics, are fun to learn about and watch, and they usually stand out which is what makes them so charismatic in the first place.

These species are the poster children for wildlife conservation.

However, while environmental activists are focusing on charismatic species, like tigers, turtles and pandas, the threat of extinction is actually being faced by the species that many don’t even know exist or recognize as dwindling.

In a recent study published in the journal Science that focused on the shockingly rapid decline of bird species in North America, we see that charismatic species are not the only species that are facing rapid population decline. Species that were once considered common are also taking huge population hits. This includes common species that many people tend to forget about or take for granted.

In a small, naturally lit office in the basement of the Science Center at Gettysburg College sits Dr. Andrew Wilson, Ecologist, Ornithologist, and Associate Professor of Environmental studies. His walls are lined with bird silhouette stickers and his bookshelves piled with field guides.

“I was kind of surprised it got so much publicity, because it’s very obvious,” said Dr. Wilson. “Anyone who watches birds could tell you that.”

However, charismatic species tend to be the species that people don’t need to be specialized in studying in order to appreciate them. Birdwatchers and ornithologists like Dr. Wilson dedicate hundreds of hours pursuing different birds while people who aren’t dedicated bird watchers, but enjoy nature, tend to appreciate the charismatic species over those that are difficult to find.

“There’s kind of this scale in conservation with things that people care about like pandas and dolphins at one end,” said Dr. Wilson, “and microbes that nobody cares about at the other.”

And he’s right. Sarahrose Jonik, a senior biology major at Gettysburg College spoke to this. “I know there are a lot of birds going extinct,” she said, “but I’m just not really a bird person.”

“I know there are a lot of birds going extinct, but I’m just not really a bird person.”

– Sarahrose Jonik, 2020

Dr. Wilson explained that species that are less noticeable aren’t as popular culturally and people don’t grow up with an affinity for them.

“LBJ. Little brown jobs, as we call them,” said Dr. Wilson. “These are birds that are small, brown and stay in vegetation. There are a lot of birds like that.”

Left to Right: “LBJs” Yellow-Rumped Warbler (PC: McKenzie Somers), female Red-winged Blackbird (PC: McKenzie Somers), and a Mockingbird (PC: Emily Kurtz)

Dr. Wilson spoke of one common bird species in particular. “The Henslow’s sparrow for example is one of our most rapidly declining populations in Pennsylvania,” said Dr. Wilson. “Most people have never even heard of it.”

So, you might ask, why do conservationists continue to focus on charismatic species?

Many arguments can be made in support of focusing on charismatic species in order to encourage biodiversity conservation. A study by Higa et al. found that conservation based on charismatic species can have positive impacts on the surrounding ecosystem and other species. This study shows that the habitats that the charismatic species were located had higher biodiversity.

However, this study only focuses on a specific habitat in a very limited scope of biodiversity conservation. Though there may be positive impacts of charismatic species focused conservation efforts, these impacts are often unintentional and don’t benefit ecosystems that are limited in charismatic species.

Ecotourism continues to encourage charismatic species focused conservation, however, the consequences tend to be negative for non-charismatic species. In South Africa, the attraction of wealthy tourists funds conservation efforts. This is great for funding, however, Hausmann et al. found that wealthy tourists are often much more attracted to charismatic species. This means areas that may have higher biodiversity but less charismatic species could be neglected since it attracts less wealthy tourists and therefore draws in less revenue.

This has influential impacts on which species are getting the best conservation efforts. According to Di Minin et al. the species that bring in the revenue, the charismatic species, are often kept separate from the surrounding habitat. This is so that they can be managed specifically for attracting tourists. This means that the species people visit less often aren’t even able to reap the benefits of living within the same habitat as the charismatic species.

For species like the Henslow’s sparrow that live in the grasslands of Pennsylvania, there are no charismatic species in their habitat to benefit from, and they’ll likely die out from the combined causes of species extinction.

Even more so concerning is the lack of public awareness surrounding the drivers of biodiversity loss, according to Dr. Wilson.

“A lot of well-informed people think its climate change, but it’s actually not,” said Dr. Wilson. “The number one cause of species extinction by far is habitat loss. Overharvesting and hunting is number two and invasive species are number three right now.”

All of these causes are driven solely by human interaction with the environment. Even though humans are the primary contributors to species extinction, people are still unaware of how large of an impact that they really have.

Biodiversity is central to development, through food, water and energy security as highlighted in a report to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs in London. The continued loss of biodiversity is not only an environmental issue. On a massive scale it will be devastating for all of us. Among the impacts are threats to food security, increases in threats to human health, and increases in environmental catastrophes like wildfires.

Through education and the spread of information, we can enlighten global citizens with the benefits that conservation of ALL species can have. It is time we begin focusing on ecosystems as a whole, and not just the species we deem as charismatic.

Appendix

Christie, M., J. Warren, N. Hanley, K. Murphy, R. Wright, T. Hyde, N. Lyons. 2004. Developing measures for valuing changes in biodiversity: Final Report. DEFRA London, London, United Kingdom.

Curran, Kelly. October 24, 2019. Personal Interview by Emily Kurtz and McKenzie Somers.

Di Minin, E., Fraser, I., Slotow, R., and MacMillan D. C. 2012. Understanding heterogeneous preference of tourists for big game species: implications for conservation and management. Animal Conservation. 16(3).

Ducarme, F., G. M. Luque, F. Courchamp. 2012. What are “charismatic species” for conservation biologists? BioSciences Master Reviews 1:1-8.

Hausmann, A., R. Slotow , I. Fraser and E. Di Minin. 2017. Ecotourism marketing alternative to charismatic megafauna can also support biodiversity conservation. Animal Conservation 20(1): 91 – 100.

Heyer, Lauren. October 24, 2019. Personal Interview by Emily Kurtz and McKenzie Somers.

Higa, M., Yamaura, Y., Senzaki, M., Koizumi, I., Takenaka, T., Masatomi, Y., and Momose, K. 2016. Scale Dependency of two endangered charismatic species as biodiversity surrogates. Biodiversity and Conservation. 25(10): 1829-1841.

Jonik, Sarahrose. October 24, 2019. Personal Interview by Emily Kurtz and McKenzie Somers.

Pennisi, E. 2019. Billions of North American birds have vanished. Science. 365(6459): 1228.

Wilson, A. October 16, 2019, Personal Interview by Emily Kurtz and McKenzie Somers.